Daniela Tapprest | Mifuko

Fashion garments these days are extremely cheap. Sounds great for fashion-lovers, right? What we pay for a product does not however pay for the whole cost of the garment; the true cost can be counted in human rights violations, such as child labour, dangerous working conditions, sexual harassment and lost lives. While the workers can’t even afford to live in slums with the minimum wage, the majority of what the consumer pays goes to the never-ending pockets of the shareholders of multinational corporations.

The Global Slavery Index estimates that 36 million people are living in some form of modern slavery today; lots of these people are making clothes for western brands. Working conditions are sometimes like in a prison. There can be up to 40 degrees of heat, no water and rats running everywhere. Despite there being international standards and national laws that should protect people, working conditions can even lead to deaths: for example, the sandblasting of fashion jeans causes workers breathing difficulties and deadly respiratory diseases. At its most extreme, workplace safety neglections can lead to horrific accidents, such as the Rana Plaza factory collapse that killed 1,138 people and injured another 2,500.

While the factory workers often work long overtime hours in these conditions, the legal minimum wage in most garment-producing countries is rarely enough for workers to live on. For example, the most common salary in Bangladesh factories is 1.26 dollars a day, which is barely over the limit of extreme poverty (1.25 dollars a day). Consequently, it is estimated that the minimum wage only covers 60% of the cost of living in a slum. Curiously, if garment workers were paid a living wage, we would pay only $1.8 extra for a t-shirt of $32.

One of the reasons why such things happen is the lack of transparency in the supply chains of fashion. Brands do not know where their products are really made, or where parts such as zippers or buttons come from, because it is very common to externalize production to the factories that agree to the cheapest price. Since companies don’t sometimes even know themselves where their products are made, it is impossible for the consumer to know that either. From the 150 biggest fashion brands in the world, 37% publish supplier lists, 18% publish their processing facilities where clothes are dyed, printed and finished, but only one brand is publishing its supplier of raw materials. The regrettable side of mass production is also that traditional artisan craft skills are disappearing from around the World. Crafting skills usually pass from one generation to the next one, and besides being an important source of income, they are a vital part of the communities’ culture.

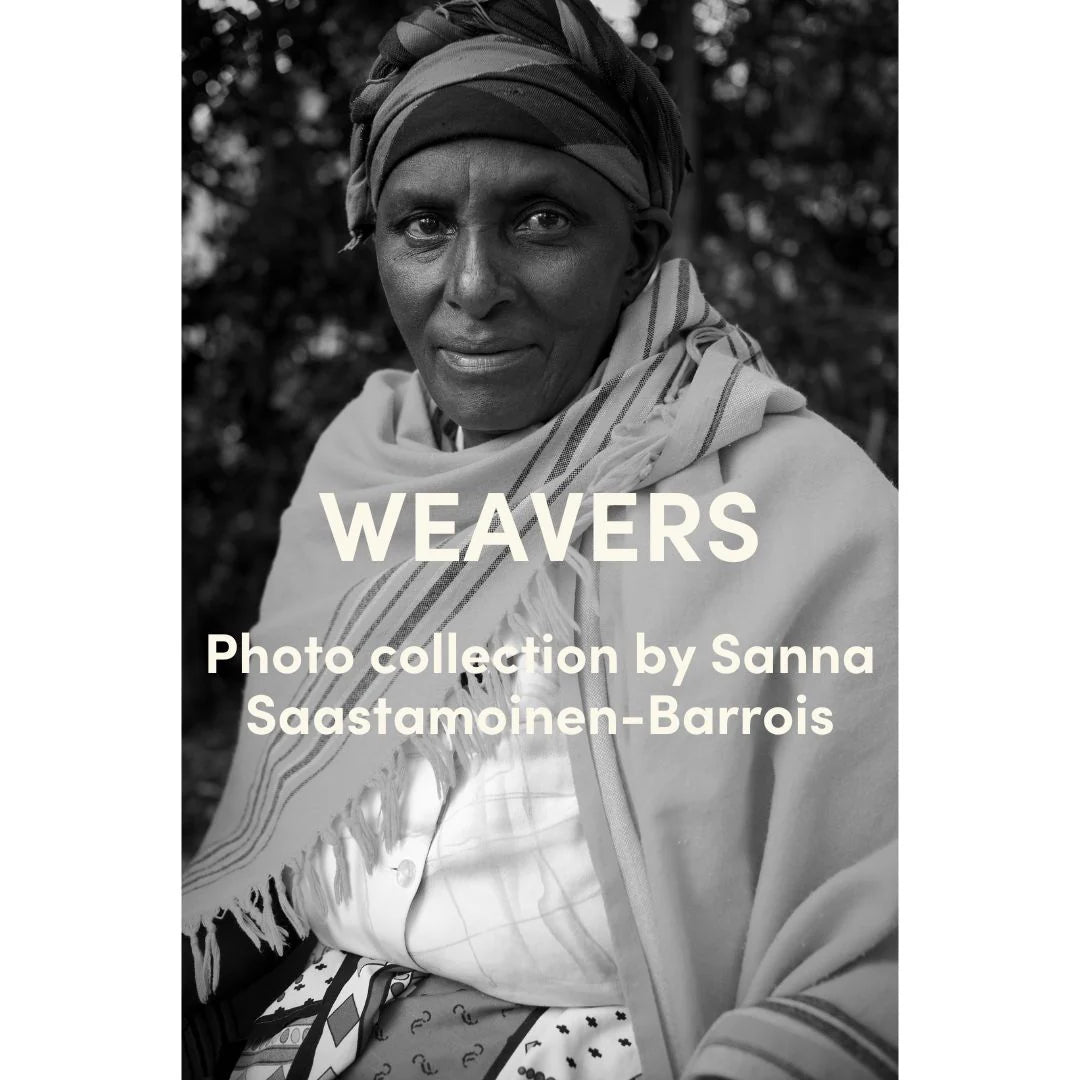

At Mifuko we are proud that we can enable the continuation of artisan skills in the rural communities of Kenya. Although the design and colours of the Kiondo baskets and bags are decided in Finland, the traditional weaving used in the baskets is the same that has been passed on from mother to daughter. Most importantly, we know exactly who has made our product and in which kind of circumstances, and we can openly share that with our customers.

Resources:

- Fashion Revolution (2019) How to be a Fashion

- Revolutionary. <https://www.fashionrevolution.org/how-to-be-a-fashion-revolutionary/>

- The Global Slavery Index (2018): <https://www.globalslaveryindex.org>

- Moilala, Outi (2013) Tappajafarkut ja muita vastuuttomia vaatteita. Into, Helsinki.